Tradition has it that in this location stood an ancient village which would have been destroyed as a result of a landslide. Following the catastrophe, survivors would have allegedly reused the wooden elements of architecture in order to build the first houses of the modern village of Fang. Is this story simply a myth, or is it an accurate historical reality?

Research history

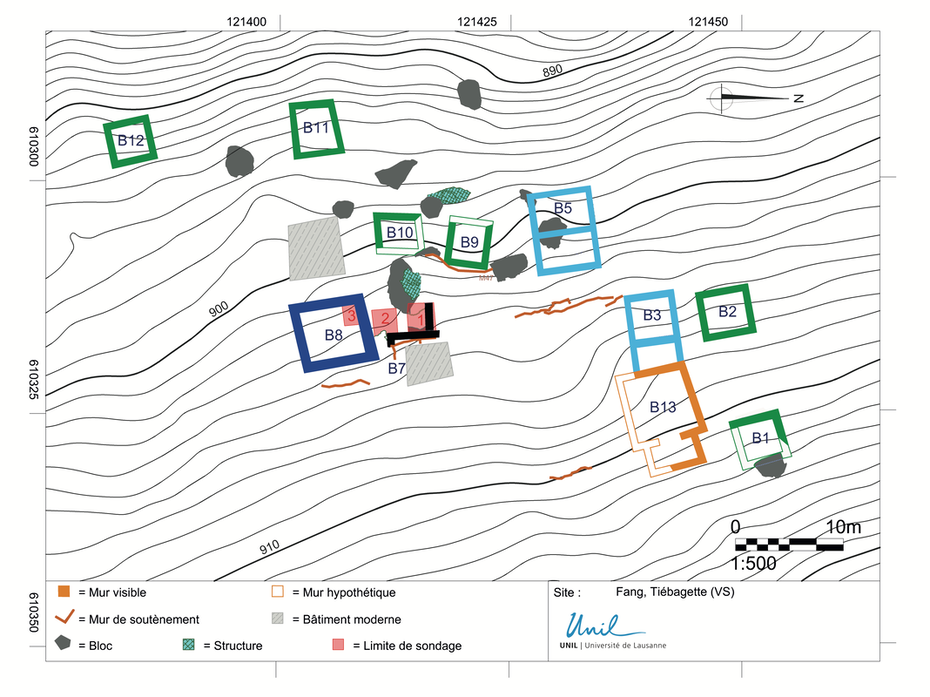

Yvonne Jollien, an ancient inhabitant of Fang, bought this parcel of forest in 1990. She was convinced that this story, which she had heard of from her dad, reflected a historical reality. Her and her husband spent numerous weeks clearing the overgrown terrain and, little by little, they began revealing the ruins of multiple dry-stone or masoned structures (fig.1).

Werner Meyer, a medieval history professor from Basel University, visited the site in 2002 to assess its nature. On the basis of the buildings’ organisation, he concluded that the site was of cantonal importance, if not more. According to him, it was essential to carry out an archaeological excavation in order to understand the organisation and economy of the settlement. This experienced professor being close to retirement at the time, he was eventually never able to begin excavating the site, and the hamlet started once again to be forgotten.

One would have to wait 2013 for Tiébagette to come to the attention of Cédric Cramatte who was a researcher at the Institut d’Archéologie et des Sciences de l’Antiquité of Lausanne University at the time. The site represented indeed a rare case in Valais, mainly for two reasons. First, villages from this period are usually long-lived, with occupations often extending up until today. Second, the walls seen in Tiébagette present an excellent state of conservation with some still standing over 2 meters high. Consequently, during spring 2014, Cédric Cramatte undertook a superficial clearing of the entire settlement with the help of more than a dozen archaeology students from Lausanne and Neuchâtel universities. This clearing allowed the team to establish a precise plan of the site. During the summer of the same year, Cédric undertakes three soundings, which provide a first stratigraphy (i.e. a succession of archaeological layers that can be dated based on the artefacts found in them) (fig.2).

One would have to wait 2013 for Tiébagette to come to the attention of Cédric Cramatte who was a researcher at the Institut d’Archéologie et des Sciences de l’Antiquité of Lausanne University at the time. The site represented indeed a rare case in Valais, mainly for two reasons. First, villages from this period are usually long-lived, with occupations often extending up until today. Second, the walls seen in Tiébagette present an excellent state of conservation with some still standing over 2 meters high. Consequently, during spring 2014, Cédric Cramatte undertook a superficial clearing of the entire settlement with the help of more than a dozen archaeology students from Lausanne and Neuchâtel universities. This clearing allowed the team to establish a precise plan of the site. During the summer of the same year, Cédric undertakes three soundings, which provide a first stratigraphy (i.e. a succession of archaeological layers that can be dated based on the artefacts found in them) (fig.2).

The hamlet’s organisation (fig.3)

The hamlet was built in a steep slope and bordering a man-built terrace (visible through the presence of multiple dry-stone walls which acted as supporting walls). Different types of structures surrounded this central square. Most buildings consisted of a single square room measuring about 3 x 3 meters (buildings B1, B2, B9, B11 and B12). Their stone foundations were topped by a wooden upper part which has today disappeared. The lower part acted as a basement or a cellar. On the other hand, the upper part could serve for the storage of edible goods, grain or hay. Alternatively, some of these buildings might have also acted as single-room houses. This type of housing could be found until the 15th century in Valais.

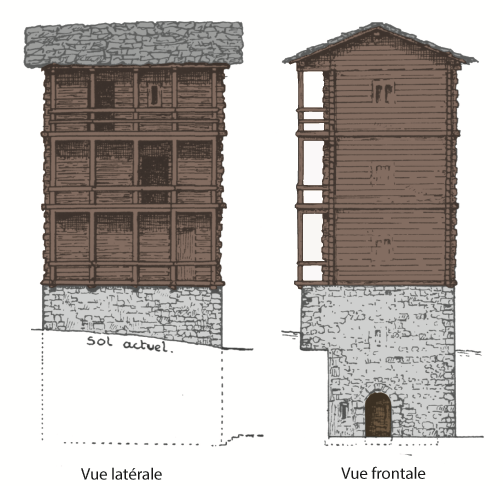

The squared building B8 distinguishes itself by its large size (7,10 x 6,40 m) and the width of its masoned walls measuring over 80 cm. A meticulous study of its walls demonstrated that they were treated with a particular technique called pietra rasa (fig.4). This method consists of a lime mortar covering the walls but leaving the protruding part of the stones visible. Afterwards, each level of stone was underlined by a horizontal line drawn in the still fresh mortar. This type of treatment was mainly used in Valais in castles and high social status houses from the 13th to the 15th centuries. The relatively large width of its walls invites us to picture the building as a multi-wooden-floored structure and to interpret it as a habitation tower. A similar structure, known as the Baillos, still existed in 1880 in the neighbouring village of Vissoie (fig.5). This building which dated to the 13th century was destroyed in 1880 by a fire.

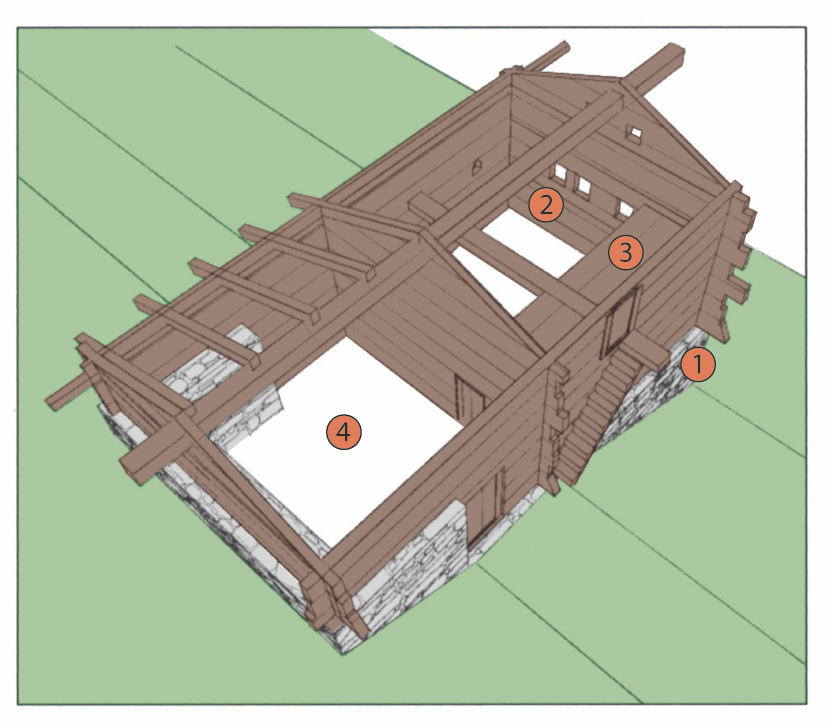

Two other structures (B3 and B5) are of rectangular plan and are constituted of two rooms on their ground level. The architecture of these buildings is characteristic of the traditional Valais house, as we know it since the 14th century from other alpine valleys such as the Lötschental (fig.6). The excavated room situated in the bottom part of the slope served as a cellar and formed the foundation of an upper wooden floor which acted as the living room. This wooden floor was accessed by the back, through the room situated in the upper part of the slope. This second stone room was furnished with a hearth and acted as a kitchen. The main beam of the living room overextended on one side of the house and allowed thereby for an external set of stairs to lie on it. These stairs permitted to access the sleeping room which was situated in a superior floor right under the roof.

Building B13 which is situated overhanging the square remains enigmatic. Its state of conservation is poor and only further archaeological excavation could allow researchers to understand its exact function. For now, archaeologists picture it as a large 7 x 7 m square room opening on its west side on another smaller 3 x 3 m room. The atypical layout of the building might suggest it was a Christian chapel.

The squared building B8 distinguishes itself by its large size (7,10 x 6,40 m) and the width of its masoned walls measuring over 80 cm. A meticulous study of its walls demonstrated that they were treated with a particular technique called pietra rasa (fig.4). This method consists of a lime mortar covering the walls but leaving the protruding part of the stones visible. Afterwards, each level of stone was underlined by a horizontal line drawn in the still fresh mortar. This type of treatment was mainly used in Valais in castles and high social status houses from the 13th to the 15th centuries. The relatively large width of its walls invites us to picture the building as a multi-wooden-floored structure and to interpret it as a habitation tower. A similar structure, known as the Baillos, still existed in 1880 in the neighbouring village of Vissoie (fig.5). This building which dated to the 13th century was destroyed in 1880 by a fire.

Two other structures (B3 and B5) are of rectangular plan and are constituted of two rooms on their ground level. The architecture of these buildings is characteristic of the traditional Valais house, as we know it since the 14th century from other alpine valleys such as the Lötschental (fig.6). The excavated room situated in the bottom part of the slope served as a cellar and formed the foundation of an upper wooden floor which acted as the living room. This wooden floor was accessed by the back, through the room situated in the upper part of the slope. This second stone room was furnished with a hearth and acted as a kitchen. The main beam of the living room overextended on one side of the house and allowed thereby for an external set of stairs to lie on it. These stairs permitted to access the sleeping room which was situated in a superior floor right under the roof.

Building B13 which is situated overhanging the square remains enigmatic. Its state of conservation is poor and only further archaeological excavation could allow researchers to understand its exact function. For now, archaeologists picture it as a large 7 x 7 m square room opening on its west side on another smaller 3 x 3 m room. The atypical layout of the building might suggest it was a Christian chapel.

Archaeological finds

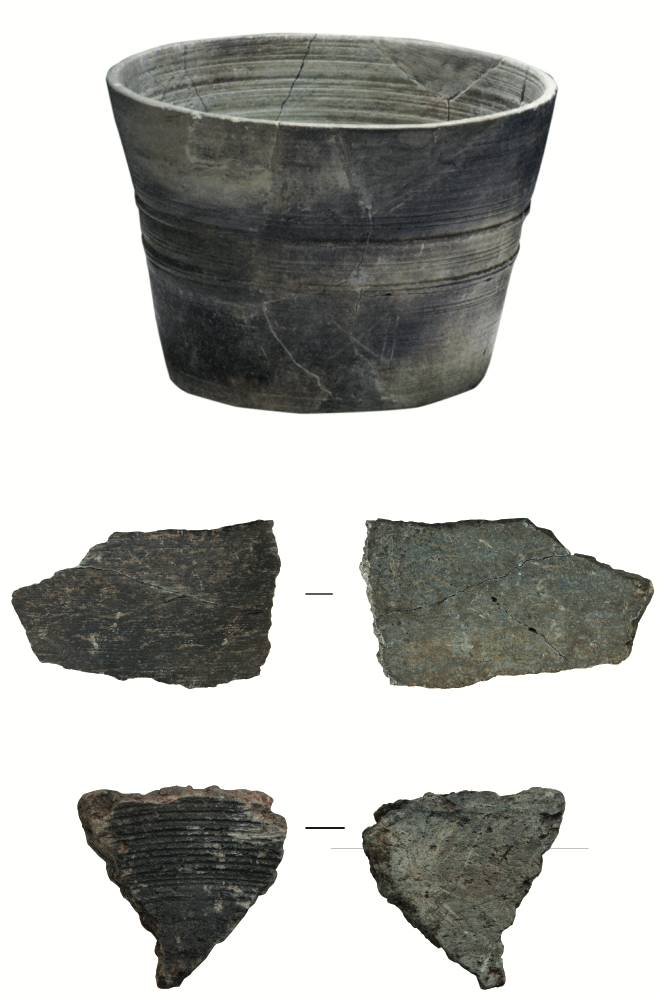

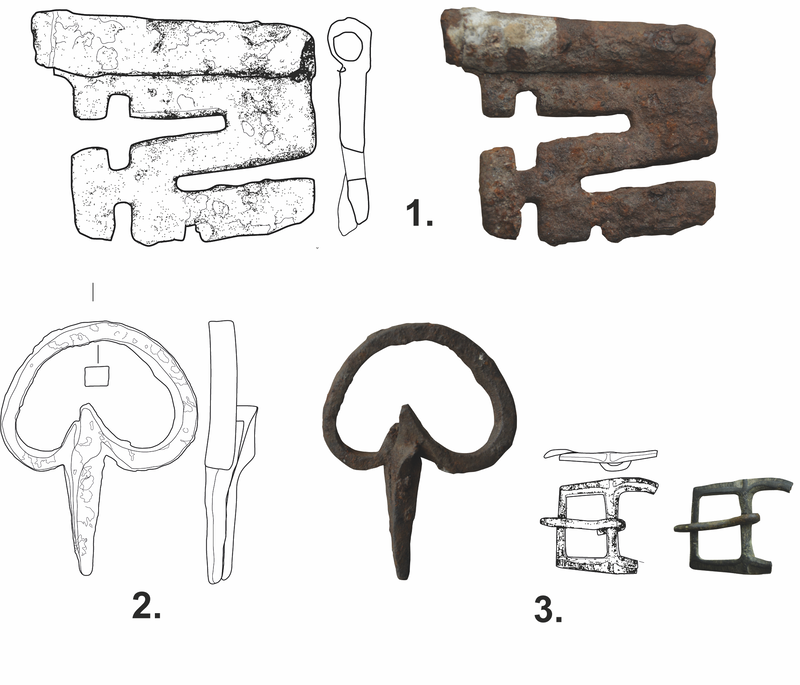

The first soundings on the site permitted to discover multiple objects dating to the medieval period. Notably, numerous fragments of a soapstone marmite were found. The stone, in all likelihood, originated from the region of Moiry (fig.7). Soapstone is known, among other things, for its high heat resistance and high heat storage capacities and is still used to this day in the manufacture of furnaces. Archaeologists have also found a couple of metallic objects among which the key blade of large iron key (13th-15th centuries) and a bronze belt buckle (fig.8). Multiple coarse ceramic shards might also date from the Middle Ages but, based on their appearance, they more likely date from a much older period such as the Iron Age (between 800 and 15 BC). Indeed, it is possible that the site was occupied since early periods as demonstrated by certain soapstone varieties which might date from the end of the Roman period (3rd-4th centuries) or at least from the early Middle Ages (5th-8th centuries).

The archaeological soundings have for now only reached the upper layers of the site. They have revealed that a building (B7) was destroyed during the 15th century as a result of a fire (fig.9). What about the other buildings? Was the fire the reason behind the abandonment of the hamlet or did a landslide indeed destroy it as the tradition has it? Only further excavations could answer these questions.

The study of the site will also allow archaeologists to understand the farming practices of this rural community. Indeed, a sounding permitted to find thousands of oxen bones and, to a lesser extent, pig, lamb, goat, and fowls’ bones (fig.10). The cutting traces visible on these bones indicate that they were part of a refuse pit linked to a butchery activity (fig.11).

The archaeological soundings have for now only reached the upper layers of the site. They have revealed that a building (B7) was destroyed during the 15th century as a result of a fire (fig.9). What about the other buildings? Was the fire the reason behind the abandonment of the hamlet or did a landslide indeed destroy it as the tradition has it? Only further excavations could answer these questions.

The study of the site will also allow archaeologists to understand the farming practices of this rural community. Indeed, a sounding permitted to find thousands of oxen bones and, to a lesser extent, pig, lamb, goat, and fowls’ bones (fig.10). The cutting traces visible on these bones indicate that they were part of a refuse pit linked to a butchery activity (fig.11).

ARAVA association and the future of the project

The Association pour la Recherche Archéologique dans le Val d’Anniviers (ARAVA) was created in 2015. Its initial goal was to permit new excavations on the site of Tiébagette, but it also aims at supporting and promoting any new archaeological research in the Val d’Anniviers. Currently, the association participates in different research project and regularly organises conferences and other events.

Concerning Tiébagette, ARAVA finalised in 2021 the preparation of its project for the study of the hamlet and is now looking for funds to materialise it. The project is structured in three parts: archaeological excavations, the restoration of the site (especially the masonries), and the promotion of the site through the creation of a visit path and the installation of didactic panels.

If you want to inquire on the progress of the project, discover our activities or even join our association, do not hesitate to visit our website or to contact us via our e-mail address.

Concerning Tiébagette, ARAVA finalised in 2021 the preparation of its project for the study of the hamlet and is now looking for funds to materialise it. The project is structured in three parts: archaeological excavations, the restoration of the site (especially the masonries), and the promotion of the site through the creation of a visit path and the installation of didactic panels.

If you want to inquire on the progress of the project, discover our activities or even join our association, do not hesitate to visit our website or to contact us via our e-mail address.

Did you enjoy your visit?

We are happy to make you discover this unique site and hope that we can count on your participation to help us maintain it (weeds tend to grow back quickly and everywhere, pathways to sink, etc.). Suggested price: 2 CHF per person. You can also choose to support our association and the excavation, restauration and promotion of Tiébagette with a more substantial donation.

This site is still under excavation / clearing, pathways are therefore not yet secured. Be careful while visiting the site. We decline all responsibility in the event of an accident.

This site is still under excavation / clearing, pathways are therefore not yet secured. Be careful while visiting the site. We decline all responsibility in the event of an accident.

(Translation: Maxence Ballif)